Your cart is currently empty!

Robert Rauschenberg and His Iconic “Combines”

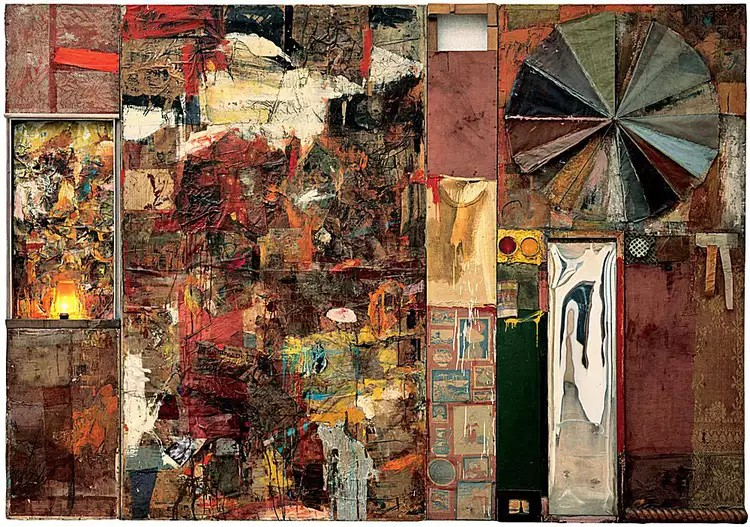

Robert Rauschenberg was an American artist whose work transformed the face of modern art. Known for using innovative materials and unorthodox techniques, Rauschenberg has been constantly defying traditional categories of art. Probably the most innovative series he ever did would be his very famous works, the “Combines.” These run from 1954 to 1964, the Combines being admired for their bold merging of painting and sculpture, which makes use of common everyday objects in their process. In these works, the boundaries of art and life were blurred, with a stretching of the limits of what art could be. With this post, we contemplate in more depth the world of Rauschenberg’s Combines-considering origins, techniques, and enduring influence on the art world.

The Origins of the Combines: Shifting Artistic Perspective

Rauschenberg began to develop the Combines during a period when Abstract Expressionism-an art style that stresses the emotional intensity and physicality of painting-was an vogue art movement. By contrast, it was the process rather than any objective in making a picture that interested its practitioners like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. They concerned themselves with the very act of painting, producing emotion by manipulating paint onto a canvas. Conversely, Rauschenberg was fascinated by incorporating the real world into his pieces instead of focusing on an entirely abstract composition.

The germ of Rauschenberg’s ideas sprang from various influences. He attended Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where avant-garde practices and a collaborative approach to the creation of art were encouraged. His teachers there were the Bauhaus-trained artist Josef Albers and John Cage, the composer whose use of chance and indeterminacy was a continuing influence on Rauschenberg. Cage’s thinking about allowing chance to determine decisions about the course an artwork would take helped Rauschenberg to embrace that element of spontaneity and even unpredictability that would prevail in his Combines.

What are “Combines”? Wedding of Art and Life

Essentially, a Combine is an artwork that fuses elements of painting and sculpture. However, at its core, the idea of a combine for Rauschenberg would involve found objects—pieces of everyday life such as furniture, photography, fabric, and even animals—becoming integral to his works. He did this by combining traditional art materials with objects from the real world, thus challenging the conviction that art had to be made only out of paint and canvas. Instead, art could be anything and everything that surrounds us.

Probably the best example of a Combine is “Monogram” (1955-1959), in which Rauschenberg used a taxidermied Angora goat, its body encircled by a rubber tire, placed on a painted wooden platform. The juxtaposition done here, using a goat-a normally applied symbol of masculinity and energy-and the flat canvas surface, creates a striking contrast both visually and conceptually. A different perspective opens with this piece of artwork-whether on the absurdity of life or the criticism of consumer culture.

Another iconic Combine is “Bed” from 1955, in which Rauschenberg used a quilt, pillow, and sheet as his canvas, which he then splattered with paint, similar to Jackson Pollock’s action painting. The intimate and domestic materials of “Bed” contrast sharply with the aggressive application of paint to indicate a conversation between the personal and the public, often discussed in tandem within the frameworks of artistic expression.

The Combines marked a seismic shift in the art world. In combining the everyday and the artistic, Rauschenberg was challenging this idea of the need to elevate art above the ordinary. Where most artists were concerned with abstraction or figurative painting, Rauschenberg’s work insisted that reality itself could be considered art. He completely blurred the line between high and low culture, bringing objects such as comic strips, street signs, and even rags of fabrics into works that showed up in leading galleries and museums.

On top of that, Rauschenberg’s Combines suggested art could be a collaborative process between the artist and the world outside him. In works like “Canyon” (1959), with its famously encased stuffed eagle, pillow, and amalie of materials, Rauschenberg showed that art could be built from a conversation with the everyday, rather than in an isolation from it. This notion of collaboration-whether with the materials themselves, the environment, or even the viewer-was one of Rauschenberg’s key proposals to contemporary art.

The Techniques Behind Rauschenberg’s Combines

One of the most interesting things that Rauschenberg does in his Combines series is his use of materials in very innovative ways. Many times, he uses a collage-like approach in layering objects and materials on top of each other to encourage viewers to approach the work from different angles. An almost palpable visual and conceptual richness invites deeper reflection through this very technique.

Rauschenberg also extended this to the materials that he used; he would use found objects or those with no apparent aesthetic value on purpose. It was the opposite, really, of Abstract Expressionism, which made conscious color and form choices. Instead, Rauschenberg allowed his materials to make choices for him, often employing chance and accident in his process. This release of materials and letting them, as it were, “speak” was typical of his manner as an artist.

In the Combines, Rauschenberg used a variety of media and techniques in addition to found objects. Many of the latter bear paint, creating a tension between the painterly and the sculptural. His works are variously infused with printmaking, drawing, and photography, further blurring boundaries between artistic disciplines.

The Cultural and Historical Significance of the Combines

Rauschenberg’s Combines came at a height when changes in culture and politics were amazingly radical in the United States in the mid-20th century. The post-Second World War era had shown the rise of consumer culture, mass media, and increased distinction between high and low art. Directly engaging this environment, Rauschenberg’s Combines reflect the dissonance between the art world and everyday life experience within the terms of consumer-driven society.

His work can also be seen as a response to the Cold War-the period of fear and insecurity. The conjunction of objects that don’t seem to go together in his Combines could be said to be a reflection of the fragmented, often contradictory quality of modern life. As such, the Combines functioned not just as aesthetic objects but as cultural critique.

Legacy of Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines

The influence that Rauschenberg has through the Combines is not insubstantial and is very far-reaching. His work helped to clear the path for later movements such as Pop Art, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art. His approach toward materials and his readiness to incorporate elements from popular culture into his art inspired artists such as Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, and Jasper Johns.

In many ways, Rauschenberg’s Combines anticipated the breakdown of barriers between art and life that would characterize much of the art of the late 20th century. It was an invitation to artists to experiment with new materials, to come out into the world, and to be at least somewhat indeterminate in the creative process. Today, Rauschenberg is regarded as one of the most significant and innovative artists of the 20th century, and the Combines continue to lie at the heart of any discussion about the developments of contemporary art.